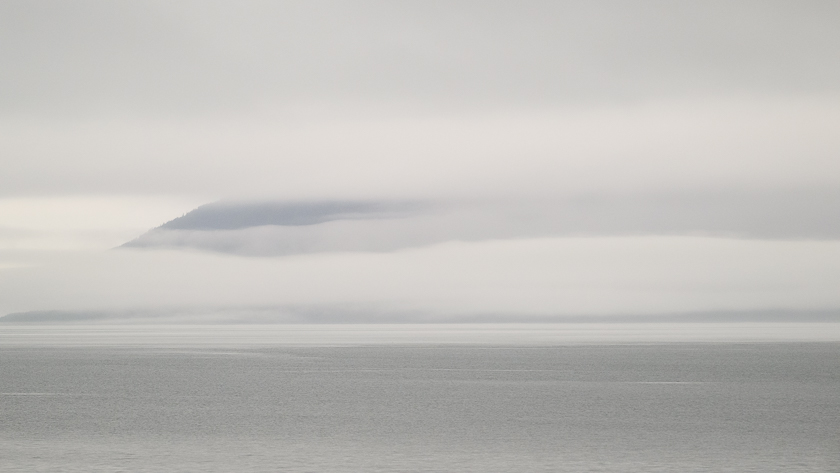

“All…day it rained. The mountains were smothered in dull-colored mist and fog, the great glacier looming through the gloomy gray fog fringes with wonderful effect. It is bad weather for exploring, but delightful nevertheless, making all the strange, mysterious region yet stranger and more mysterious.“

JOHN MUIR AT THE FACE OF MUIR GLACIER,

JULY 27, 1890

Being prepared to deal with rainy weather in southeast Alaska is critical to an enjoyable and safe trip. Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve is no exception. If anything, it is essential.

A trip last August was a good example of this importance. Eight straight days of consistent rain in Glacier Bay’s backcountry might have dampened the spirits for some, but for Carol and me, and our friends Billy and Shari, who joined us later, the seemingly constant rain didn’t bother us in the least.

Despite all the marketing by outdoor clothing companies to make you think that your three-layer, super-high-tech, breathable rain gear will keep you dry, I can tell you confidently that it will not keep you dry when it rains for such an extended length of time as we experienced. For that reason, we ditched our expensive, breathable waterproof rain gear for old-fashioned, low-tech rubber jackets and bibs. We stayed warm and completely dry.

“Birthday Island”

Our adventure started with the exploration of the Beardslee Islands of the park, an area of the national park where we have made numerous trips (above photo). Fog and rain, with a few hours of welcomed partly cloudy skies with low winds, made the paddling easy. For our first night, we traveled to a very small unnamed island, probably about 1.5 acres in size. We unofficially named it Birthday Island as Carol, and I would be celebrating my birthday there.

Campers in the Glacier Bay National Park backcountry are encouraged to cook and eat in the intertidal zone at least 100 yards from their tent and food storage area. In addition, food and other scented items should be stored in a bear-resistant food container (BRFC). The method ensures that incoming tides will erase all traces of your food preparation and dining. Carol found us a perfect table to prepare and eat dinner. Rain during dinner didn’t dampen our spirits due to our staying dry in our rubber-coated rain gear, though I’m sure the birthday celebratory glass of wine didn’t hurt either.

Challenge – find an abandoned fox farm

Those who know me know that I LOVE maps and backcountry navigation challenges. It’s an excuse to satisfy my desire to explore. This love was long before the advent of GPS. An altimeter and compass were my tools of choice back in the technology stone age. Those navigation instruments served me well for many years, but I must say GPS has made it easier.

Part of any trip’s homework is to find a navigation challenge. The challenge for this trip was to see if we could find the remains of an abandoned fox farm from the early 1900s on one of the dozens of islands in the Beardslee Island group. While this sounds simple enough, it still meant studying written accounts of the approximate location, consulting both modern and historical maps, checking satellite images for clues, and consulting tide tables to make sure we knew when it was best to land on the island.

We passed 4-5 islands on the way. It is important to keep tabs on each one you paddle past, as they all look the same. Eventually, we made it to the island where we believed the farm once was, but we knew that was only the beginning of our exploration.

The forest edges of the Beardslee Islands appear to be impenetrable with bushes and shrubs, but once you get past them, the island’s forests open up to a moss-carpeted and lichen-rich landscape.

The bright, green color of lungwort (Lobaria pulmonaria) indicates that it is saturated with water. This lichen was photographed near the abandoned fox farm in the Beardslee Islands of Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve. The presence of lungwort is an indicator of a rich, healthy ecosystem. Lungwort is sensitive to air pollution.

After a brief exploration of the forest, we finally found the first of two buildings of the long-abandoned fox farm.

This abandoned building sits in the rainforest at the site of a historic fox farm on an unnamed island in the Beardslee Islands in Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve. Several significantly weather-damaged small buildings are all that remain of the operation. Fox farming in Southeast Alaska began in the early 1900s with the introduction of Russian arctic foxes, which were prized for their snow-white fur. The Great Depression caused most of the fox farms to cease operations. The National Park Service reminds visitors not to take or move historical objects and that weather-damaged structures like those found at this site should not be entered due to the likelihood of imminent collapse.

While it would have been nice to spend more time, we needed to head back to the island that we used as our base.

View from our base camp on “Birthday Island.”

The “Boneyard”

It was time to move on to our next destination in the Beardslee Island group. While it may seem odd to be packing the kayaks so far from the water, we were timing the packing so we would be done by the time of the rapidly encroaching tide would be lapping at the kayaks when it was time to head off to the next island. We welcomed the few hours of patches of blue sky during the paddle.

A few hours later, we arrived at another unnamed island that we named “The Boneyard.” We named it that for the numerous sea otter skeletons that we found there.

Despite our ominous unofficial naming of the island, we were treated to a beautiful dinner sunset over Eider and Strawberry Islands.

Heading up bay – The East Arm

After resupplying with food back at Bartlett Cove, the park’s headquarters, we boarded a water taxi/sightseeing boat that would drop us off 46 miles further up the main portion of Glacier Bay. For this portion of the trip, we were joined by our friends Billy and Shari.

Our plan was to explore the East Arm (aka Muir Inlet) of Glacier Bay. We picked the East Arm for its solitude and lack of cruise ship traffic. Despite the seemingly never-ending rain, it proved to be a good choice.

Rain and fog didn’t hamper our wildlife viewing on the way to our dropoff location. We saw whales, sea otters, sea lions, and numerous sea birds like puffins and cormorants.

A sea otter (Enhydra lutris) floats on its back in the Sitakaday Narrows of Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve. Sea otters, a keystone species of the North Pacific, were almost entirely eliminated by commercial fur hunters in the early 1900s. While they received wildlife protection in 1911, it wasn’t until the early 1990s that sea otters were observed to inhabit Glacier Bay for the first time. As the most abundant marine mammal in Glacier Bay, current estimates put the number of sea otters at 8,000. While orcas are the primary predator of adult sea otters, newborns are preyed upon by bald eagles. Sea otters are positively impacting the kelp forests as the otters protect the kelp forests from excessive grazing by the sea otters’ prey.

A humpback whale (Megaptera novaeangliae) dives near Young Island in Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve. Humpback whales, weighing as much as 40 metric tons, can stay underwater for up to 20 minutes. Whales come to Glacier Bay National Park to feed on the abundant krill and small schooling fish found in its waters.

Steller sea lions (Eumetopias jubatus) relax at their haul-out on South Marble Island in Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve. Large male sea lions will compete to mate with females at outer coast locations in the park, with the unsuccessful or immature bulls gathering at haul-out areas like South Marble Island. South Marble Island is also known for its colonies of nesting birds, including tufted puffin, pelagic cormorant, black-legged kittiwake, pigeon guillemot, and common murre.

A tufted puffin (Fratercula cirrhata) flies towards South Marble Island in Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve. For most of their lives, tufted puffins live on the open ocean, far from shore, only to return to the nesting cliff where they hatched. Underwater, they open their wings and “fly,” diving as much as 360 feet deep. Tufted puffins will also consume their prey underwater unless they bring food back to the nest’s chicks. When returning food to the nest, they can hold as many as 20 fish in their bill crosswise. Tufted puffins are heavy for their wing size. To fly, they beat their winds upwards of 400 times a minute to stay in the air.

A pelagic cormorant (Phalacrocorax pelagicus) stretches its wings on boulders at South Marble Island in Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve. Pelagic cormorants can hold their breath for 2 minutes and dive as deep as 138 feet to catch fish. They use their wings to steer while diving. South Marble Island is also known for its colonies of nesting birds, including tufted puffin, pelagic cormorant, black-legged kittiwake, pigeon guillemot, and common murre.

Eventually, we reached our dropoff point, where the water taxi carefully lowered our boats onto the beach. We had thought through how we would pack the kayaks prior to being dropped off, so packing them was fairly quick. After several hours of easy paddling with the incoming tide going in our direction of travel, we reached a place that I thought would be a great spot to camp. It turned out to be a most excellent spot, with nice views and interesting hiking in the forests behind our campsite.

Landfall and our home for the next several nights

Carol contemplates the misty, foggy vista of the Muir Inlet of the East Arm of Glacier Bay.

Almost skeleton-like, a fallen moss-covered tree is slowly absorbed into the floor of a temperate rainforest along Muir Inlet. Glacier Bay’s forests consist of evergreen trees like western hemlock and Sitka spruce dripping with lichens and mosses. A thick layer of vegetation, such as fungi, liverworts, and wildflowers, covers the forest floor.

A pink bonnet (Mycena rosella) rises out of the moss-covered rainforest along Muir Inlet in Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve. Its growing season is autumn, and it is found exclusively on coniferous needles. Mycena are important decomposers of a wide variety of plant materials.

The gang during a dry moment, Shari, Billy and Carol.

Carol warms her hands on a cup of coffee prior to moving on to our next campsite.

Good navigation skills are a must when kayaking in Glacier Bay National Park. Don’t just depend on a GPS. I find real maps, and studying those maps prior to departure is helpful.

Carol takes a paddling break on the water

Carol kayaks past a small iceberg floating in the Muir Inlet of Glacier Bay National Park. This piece of glacial ice is technically not an iceberg due to its small size. The size category for an iceberg is huge, with the height of the ice must be greater than 16 feet above sea level, a thickness of 98-164 feet, with a coverage area greater than 5,382 square feet. Next size down is bergy bits (height less than 16 feet above sea level but greater than three feet), then growlers (less than three feet above sea level – the size of a truck or grand piano), and then brash ice. The piece of ice is from the retreating McBride Glacier. Recent research determined that there is 11% less glacial ice in Glacier Bay than in the 1950s. Still, even with the earth’s rapidly changing climate, Glacier Bay is home to a few stable glaciers due to heavy snowfall in the nearby Fairweather Mountains.

Billy snagged a small piece of the floating ice for his nightly bourbon cocktail. It was a great idea, but by the time we got to our new camp, it had melted. Damn it!

These interstadial tree stumps in the Muir Inlet of Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve may look unimpressive, but they are important witnesses to the park’s glacial history. Glacier Bay National Park in Southeast Alaska is the largest known repository in North America of interstadial wood from the Holocene period, which began about 11,700 years ago and continues today. Interstadial wood is not fossilized; rather, it was frozen and unfrozen when glaciers advanced and receded in the bay. The forest was sheared off when the glacier advanced but left the stumps behind. Scientists can study the rings of these trees for clues to the glacial timeline of the park. Some stumps in the park date to over 9,000 years ago, and twigs date to 13,700 years ago.

It’s not unusual to have a visit by bears. I prepared for it by carrying bear spray as we have yet to have a trip to Glacier Bay, where we didn’t make reasonably close contact with a bear and a few times a little too close. While I won’t jump into the debate on the merits of bear spray vs. a gun, just know that bear spray has been proven to be more effective and safer than a gun. Storing food properly, using common sense in picking camping spots, and behaving properly in a bear’s presence is equally important, if not more important. On this trip, we had a grizzly pass by our camping spot on the beach. He appeared to be eating the barnacles exposed by the low tide. I can’t imagine they were particularly tasty, but since salmon wasn’t running then, beggars can’t be choosers. He made his way down the beach, returning past our tent a few hours later. I suspect he probably does that route every day.

A grizzly bear (Ursus arctos) disturbs glaucous-winged gulls (Lars glaucescens)on the beach near where we camped.

A grizzly bear (Ursus arctos) pauses on his beach stroll to take a glance at our tent. He immediately moved on and showed no interest in the tent. Grizzly bears can be found in every part of Glacier Bay. It is common to see bear activity of bears along the park’s 1,100 miles of coastline. Bear-resistant food canisters (BFRC) are required to store food for backcountry campers. The use of BRFCs has greatly reduced human-bear incidents in the park.

One of the highlights of our evenings was the reading of a Robert Service poem by Billy. His deep, perfect-for-radio voice was ideal for his post-dinner readings. My favorite is “The Cremation of Sam McGee.” Listening to Service’s poetry in the environment he describes brings a special extra dimension to his literary works.

Billy reading Robert Service poetry with Carol and Shari on the “living room couch.”

“South… gale-force winds…(indiscernible)…small craft warnings…”

Each evening throughout the trip, you would find me on the tallest spot near the beach with my arm stuck high into the air, holding and rotating the small VHF radio used to get the twice-daily weather forecast broadcast from park headquarters for this part of Alaska. The broadcast is always scratchy, broken, and not unusual to be unreachable. On our last night in the backcountry, the broadcast was breaking up badly, with the only words discernable being gale-force winds and small craft warnings. This was troublesome news for us as the next morning, we had to paddle several miles to our water taxi pickup point. Equally troubling was that our tents were on a south-facing beach on the open/main part of the bay, meaning that we would bear the brunt of any storm. My fears were confirmed by texting a satellite message to Leah with Glacier Bay Sea Kayaks, our sea kayak rental provider. Luckily, the winds didn’t come during the night hours, and even more luckily, they weren’t near as bad as we made our way to our pickup point.

Did I say that it rained on this trip? Thank god for rubber!

What a difference a day makes

Wouldn’t you know it, when we awoke in civilization, we were greeted by brilliant sunshine, as seen in the photo below of boats anchored in Bartlett Cove, the park’s headquarters. It was like we had arrived in a completely different place. We had a few hours to kill before catching the ferry to Juneau, so we explored the trails and interpretive exhibits near the park lodge and campground. It was a good way to slowly integrate ourselves back into the modern world after having spent time in the wilderness.

Boats take advantage of calm waters to anchor in Bartlett Cove. The Bartlett Cove Public Use Dock is the primary entry and launch point for vessels to Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve. Boaters should refer to the park’s website for specific rules and regulations for operating a vessel in Glacier Bay National Park.

Light filters through the lush spruce and hemlock rainforest on the Forest Loop Trail in Bartlett Cove of Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve. The easy 1.1-mile loop trail through the forest that sits on a glacial moraine is popular for birding, wildflowers, and other wildlife. Glacier Bay National Park is located in southeast Alaska. The park is also an important marine wilderness area known for its spectacular tidewater glaciers, icefields, and tall coastal mountains. The park, a popular destination for cruise ships, is also known for its sea kayaking and wildlife viewing opportunities. Glacier Bay National Park is home to humpback whales, which feed in the park’s protected waters during the summer, both black and grizzly bears, moose, wolves, sea otters, harbor seals, Steller sea lions, and numerous species of sea birds. The dynamically changing park, known for its large, contiguous, intact ecosystems, is a United Nations biosphere reserve and a UNESCO World Heritage site.

LINKS:

- PHOTO GALLERY: Glacier Bay National Park & Preserve

- PHOTO GALLERY: Lamplugh Glacier landslide

- BLOG: Glacier Bay National Park – Witnessing change

- BLOG: Massive landslide pours onto Lamplugh Glacier

- BLOG: Glacier Bay images published in Alaska Geographic book

- VIDEO PANORAMA: Glacier Bay’s enormity is hard to fathom