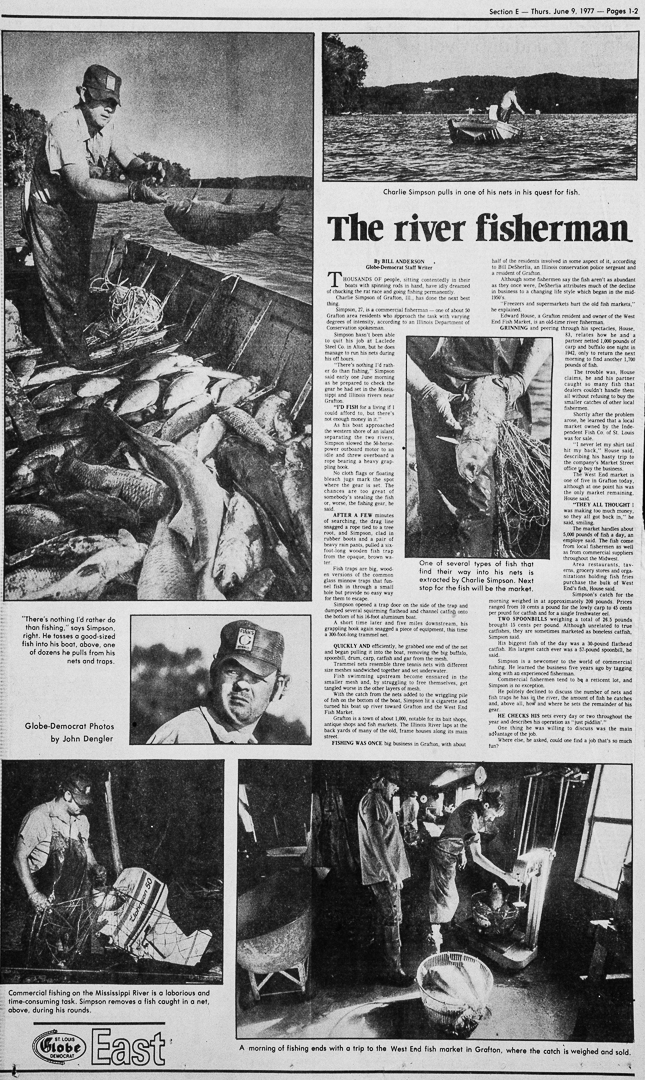

A few weeks ago, I made a scouting trip to the Loess Bluffs National Wildlife Refuge in northwest Missouri near the Nebraska/Iowa/Missouri border. I use the word “scouting” trip as I knew I was traveling there long after the big migration of waterfowl (and the accompanying bald eagles) had passed through. Still, I wanted to make the trip because I have wanted to check the area out for over a decade so I knew what to expect when I would return during the height of the massive migration of millions, yes millions of birds.

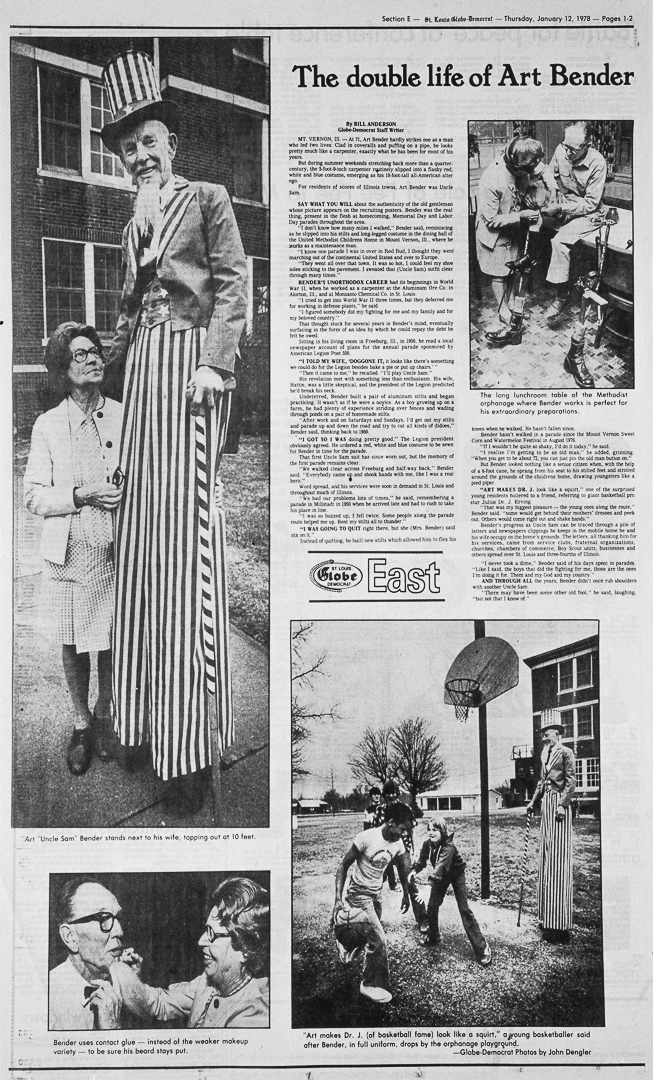

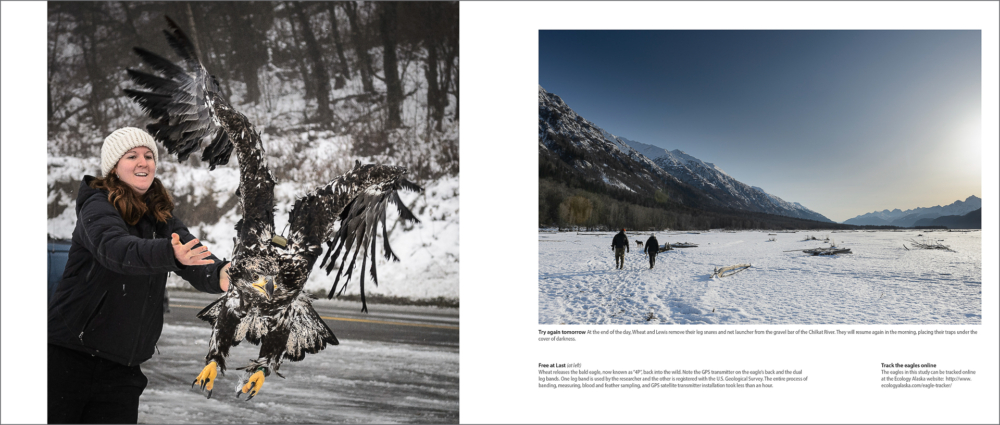

I found the refuge (formally known as Squaw Creek) largely deserted, not only of people but of waterfowl. Outside of a few waterfowl stragglers, a few bald eagles (likely resident), and a coyote or two. Of the 7,440 acres of the frozen landscape, I found only one small pool of water that wasn’t frozen over. It was quite a distance, and any attempt of trying to get closer to the waterfowl would have caused them to take flight and expend their much-needed energy. As the saying goes, if all you have are lemons, you make lemonade, which is what I did. The results are nothing to shout about, but it allowed me to get a feel for the possibilities for future trips to the refuge.

I look forward to returning.

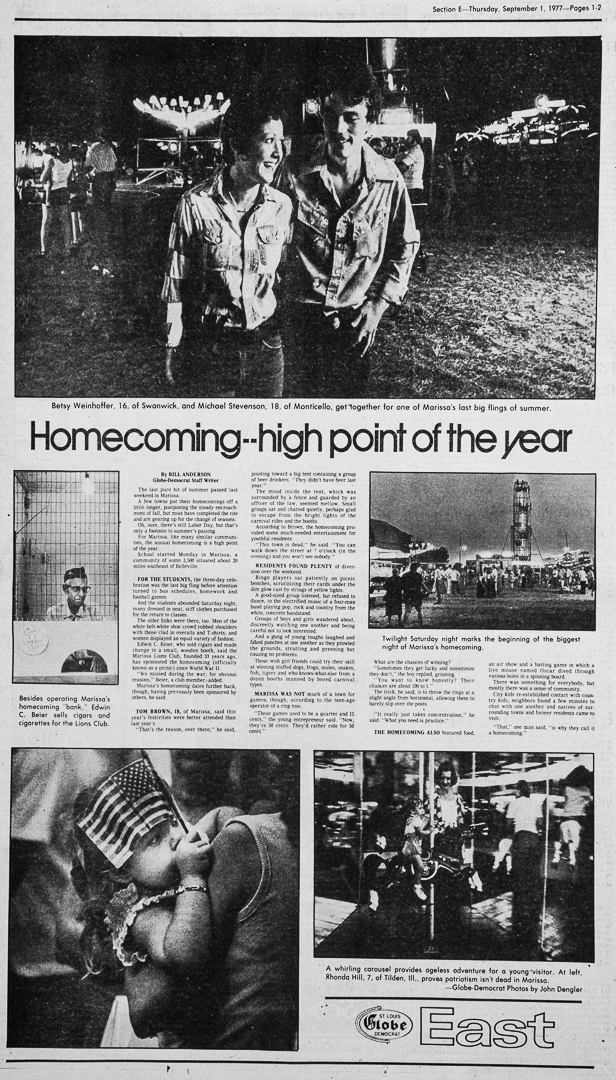

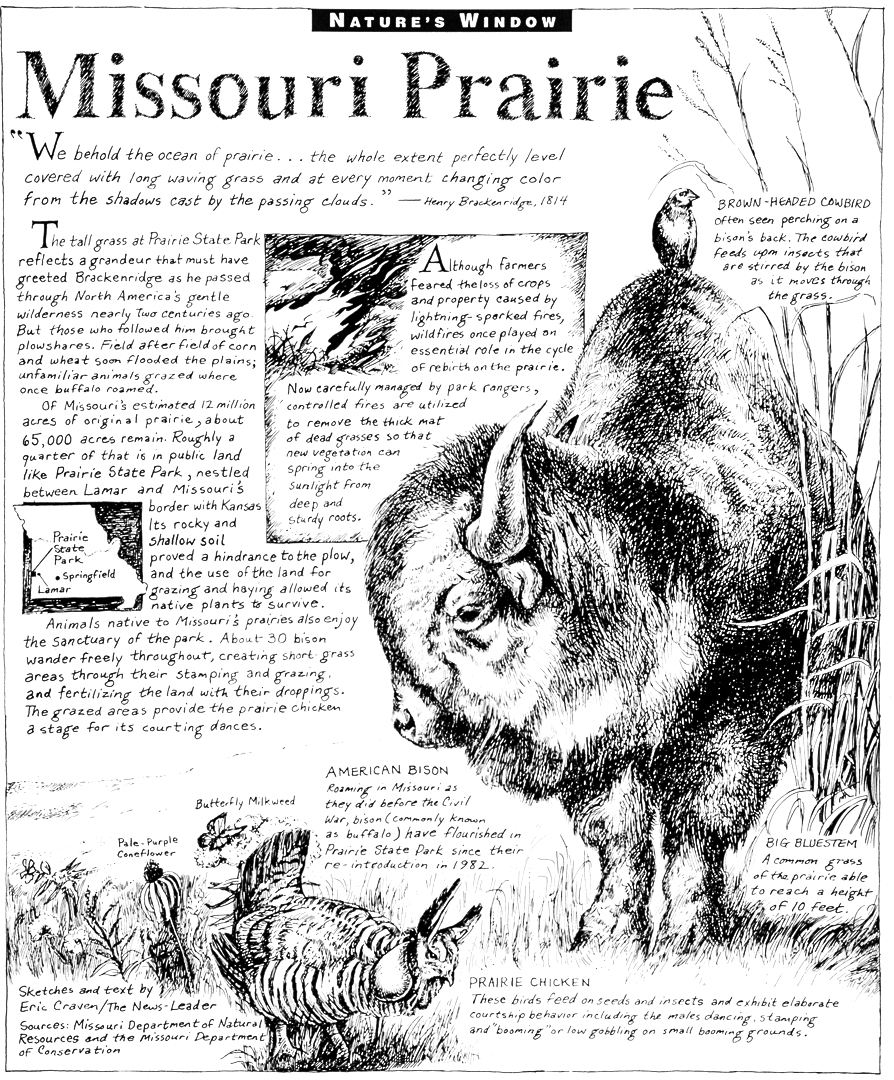

Fall and Spring migration can bring millions of snow geese to the refuge. Also, bald eagles and an occasional golden eagle pass through the area during the fall and winter months. The 10-mile auto tour around the waterways and marshes is a great way to spot birds of prey, waterfowl, beavers, otters, and muskrats.

VIEWER’S TIP: Eagles are less likely to fly away if you view from inside your car. Your car is a great “mobile” blind.

VIEW PHOTO GALLERY of all my Loess Bluffs National Wildlife Refuge photos

Be the first to know ‘Follow’ Dengler Images on Instagram @DenglerImages or follow my Twitter feed to know when I post iPhone reports from the field.