I was not familiar with the nature magazine Orion until recently. The 30-year old magazine is known for its thoughtful nature writing and its coverage of environmental and cultural issues. Orion’s website states that “Orion’s mission is to inform, inspire, and engage individuals and grassroots organizations in becoming a significant cultural for for healing nature and community.” Headed by Editor-in-Chief Chip Blake, Managing Editor Andrew Blechman, and Editor Jennifer Sahn, the magazine has twice won the prestigious Utne Independent Press Award for General Excellence, most recently in 2010.

It has published such authors as Wendell Berry, Barry Lopez, Terry Tempest Williams, Michael Pollan, Mark Kurlansky, Derrick Jensen, Sandra Steingraber, Gretel Ehrlich, Bill McKibben, Barbara Kingsolver, Rebecca Solnit, William Kunstler, Cormac Cullinan, Erik Reece, James Howard Kunstler, and E.O. Wilson.

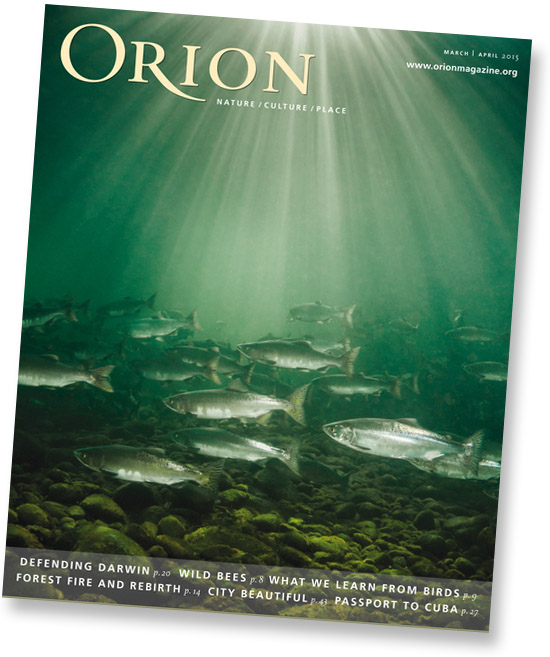

I was impressed with its attention to image selection and the clean but powerful visual presentation. As such, I’m especially pleased to have one of my bald eagle photographs, taken at the Alaska Chilkat Bald Eagle Preserve, published in the March/April 2015 edition. The image accompanies an essay by Lia Purpura, writer in residence at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County. Purpura’s essay “My Eagles” was described in the index, “Strip away the cultural baggage, and you have a bird buoyed aloft by it its own meaning.”

Orion, a bimonthly, has no advertising in its pages. As a former magazine creative director, I was interested to learn that it is supported by 30% from subscriptions and sales, and 70% from donations. That’s an intriguing publishing model in today’s turbulent magazine publishing industry. The fact that Orion has been publishing using the model for 30 years says something about well it works for the magazine.

If you are not familiar with Orion magazine, check it out.

LINK