Carol and I lost two very close friends this past year. First in early February we lost Betty McDougall, wife of Angus McDougall. Then, several weeks ago, Betty’s husband Angus “Mac” McDougall, an icon in the world of picture editors, photojournalists and photo educators, passed away.

Days after his death David Rees, director of the photojournalism sequence at the Missouri School of Journalism, and I wrote a story marking Mac’s death for the upcoming September issue of News Photographer magazine, published by the National Press Photographers Association. What follows is a portion of that article where I reflect on the personal relationship that I had with Mac.

Those of you who are friends of Mac and Betty or supporters of photojournalism, please consider a donation to the Angus and Betty McDougall Center for Photojournalism Studies.

Angus McDougall was many things to people, but in my case he was simply my best friend.

Like most, I respected his work ethic, insistence on excellence, intolerance of laziness, phoniness, and pompousness, and his willingness to state it. We liked to say he had one hell of a bullshit detector set on ‘very sensitive!’

Of course you really couldn’t love Mac and not come to adore his wife, Betty. Betty was Mac’s partner — not just a spouse or a life partner — but a true partner in everything. His work was her work and she was as dedicated and perfectionistic as he was. He used her as a sounding board. She typed all of his work (he was a single-finger typist), edited his writing and was his most honest critic and editor (she too had a very sensitive bullshit detector, but her way of stating it made you feel good about your self, at least until you thought about it) and she wasn’t above leveling that honesty at Mac, who with a smile on his face would symbolically twist a knife in the air. He trusted her insight over all others. It was Betty who had the photographic memory of all of Mac’s students and colleagues – she could tell you who they were, when they graduated and where they went – not to mention much more personal information. Mac would freely admit that if there were papers that would be needed later, he would entrust them to Betty so they could actually be found. Betty was always thoughtful of Mac’s students; in fact it was Betty who started the tradition of dinner at their home for photo-j students following their final exam. It was Betty who made Mac more accessible, more human.

Mac and Betty grew up in Waukesha, Wis., knew each other in grade school and became high school sweethearts. They fell in love and were together from that point on – through college, Mac’s professional education in photography (which his father thought was “crazy” and Betty whole heartedly supported), throughout his career at the Journal, IH, and the university, and the remainder of Betty’s life. Betty assisted him on photo feature stories, holding lights, and breaking down barriers with new subjects. They were married for 70 years and for the past three decades or so they used the same wedding anniversary card. They each knew what the card would say. Only a new date would be written on the nearly filled-in card. As would be expected, losing Betty in February was tantamount to losing a large part of himself.

Over the last couple of years Mac focused much of his energy and dedication to assuring that, though Betty had advanced Parkinson’s disease, her wish to remain in their home was realized. To accomplish this goal he did many un-Mac-like things. He rolled her hair and took over the cooking and cleaning. We even saw him once in Betty’s frilly little apron. It was a sight to see with Mac in the kitchen and Betty with drill sergeant precision instructing from the living room.

Mac and Betty knew how to have a good time, too. A McDougall party in their younger years could involve jumping on pogo sticks on their front lawn (documented in home movies), or the nose-nickel game – lying flat on your back on the floor with a nickel on your nose and trying to inch it off with your tongue. Pictures from this parlor game were published in LIFE magazine. By the way, Betty won that contest.

Mac was very humble about his professional awards and kept most tucked away in a drawer or buried on a shelf. Going through his home following his death, his son Angus “Craig,” daughter Bonnie and daughter-in-law Kathleen, found award after award. They were puzzled as to why they never knew of these accolades. These weren’t just any awards – but awards whose previous recipients included the likes of Winston Churchill (he was once a reporter), Walter Cronkite, Ted Koppel, and James Nachtwey. His children didn’t know about these awards because Mac just didn’t talk about it. It was always about the work, not the recognition. Mac saw awards and honors as the byproduct of excellence; no big deal because that level of performance was what he expected of himself, and others, every day.

This humility dates back to his preprofessional days. My wife Carol and I had known Mac for years before we discovered that he even received two life saving awards. One was an award for heroism from the Boy Scouts for saving a life. Who was the person he saved? Betty, when she fell through ice as a youth. Later he would attempt to save another life when he was a harbormaster in Fish Creek, Wisconsin, but the person later died. Mac’s son inherited his dad’s lifesaving traits. Angus Craig McDougall was awarded two Silver Stars, three Air Force Distinguished Flying Crosses, and seven Air Medals for rescuing downed pilots and crew from the front lines in Vietnam.

According to Craig and his sister, Bonnie evenings at the McDougall household started with a requisite happy hour, followed by dinner. Mac once reminisced, “Betty always made dinner a family affair, and I probably made it a board meeting. If I got too excited, our Siamese cat would bite my ankle to the delight of the kids.” Occasionally, they might have as a dinner guest, perhaps a visiting photographer from LIFE magazine. According to Craig, “In those days having a LIFE photographer over for dinner was like having a rock star visit today.”

One of the secrets to their long life, besides the nightly gin martini, prepared in a perfectly chilled glass, was their daily walk – they would drive to a different part of Columbia and walk for an hour, and then return home for breakfast. Betty served as the scout for locations and routes and carefully recorded their walking mileage.

Mac’s quirks are memorable – his hand resting on his head as he thought. A 1978 News Photographer article described it as “McDougall places the flat of his hand carefully on top of his head. He holds it there for seconds at a time in deep thought, almost as if he is hoping the answer will seep from his palm into his brain.” or his habit of lecturing with the hidden toothpick in his mouth. Students would panic as he inevitably became agitated, wondering if he would swallow the darn thing. It is only appropriate that there is already a rumor going around that one of those toothpicks was placed in his mouth before his body was cremated. This is probably an urban legend destined to stay a mystery.

I will miss “iChatting” with him on the computer. What a technologically savvy guy he was! He certainly shattered the stereotype of the computer illiterate older adult — How many people in their nineties are using Photoshop, InDesign, and working collaboratively over the internet on a book project. He especially liked this because you could talk for hours and not have to pay for a “long distance” phone call.

Mac and Betty and my wife Carol and I were good friends who liked to hang out with each other as much as we could. It was a friendship that we treasured, and unique given the roughly 37 year age difference between us. Age simply was not part of the equation. It is a wonderful example of friendship being ageless. We believe our relationship was a testament to their youthful outlook on life — they were always open and younger than their chronological years. While we hoped they would be with us forever, the four of us knew that their time would come sooner rather than later and as always, they openly discussed their life and eventual deaths.

Mac’s daughter-in-law Kathleen put out word the morning of his death that Mac had taken a turn for the worse and wasn’t expected to make it through the day. I made the familiar drive from Springfield to Columbia to be with him.

Among the things I told him as I held his hand moments before his peaceful death was the influence he had on others – family, students, friends and colleagues and what a wonderful gift that was; how we all loved him for how unselfish he was in his time and support. But I also told him that there’s a whole world of people, not just students and professionals, but also the people he met and photographed, the readers who were moved by his work and the work of his students whom he equally touched in an indirect way.

I knew this was the message that all of us would have wanted to tell him.

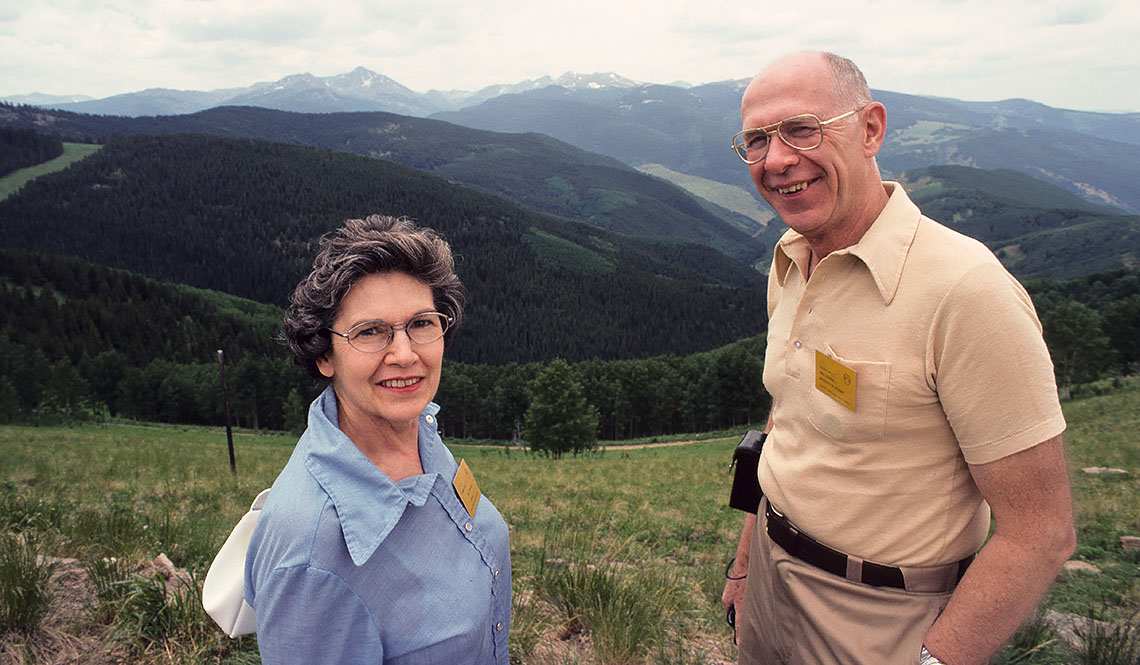

ABOVE: Betty and Angus McDougall atop a mountain at the Vail ski resort during the 1977 NPPA connvention in Vail, Colorado. (photographer unknown)

LINKS

- Angus and Betty McDougall Center for Photojournalism Studies

- Angus McDougall to Receive Missouri Honor Medal

- Pacesetters in Corporate Journalism: International Harvester magazines–reaching readers through photojournalism

- Photojournalism Legend Angus W. “Mac” McDougall, 92

- Photojournalism Legend and Former POYi Director Passes at Age 92

- Angus McDougall, a Legendary Force in Photojournalism, Dies